An update: January 2023

The writing was really in the table from the moment that I sat down with DEFRA. If you read the original post below you will see that for all the work that The Real Bread Campaign did the 1st option given was the one that happened. According to some reports the sourdough bread market will be worth 7.3 billion by 2027. So yes the definition of sourdough is still really important, especially as consumers are prepared to pay more as the recent reports indicate that the price of sourdough is increasing.

Newspapers certainly like to report the news as though it happened instantly, but the reality is that Sustain and The Real Bread Campaign have kept up with meetings and kept the pressure on for change to bread legislation for years after I facilitated the initial meetings with DEFRA. The Telegraph reported that DEFRA launched its investigation into fake sourdough as though the announcement seeking views in updating the 1998 bread and flour regulations was instant news, and I almost spat my real sourdough toast out laughing as I read the feature (it was actually too good to spit out,) however, long hard slog that took 8 years to get the industry to self regulate isn’t quite as exciting I suppose.

I still hold with my reservations of how an industry could be policed if bakers had to ” prove,” that there sourdough is real, but according to the Independent The real bread campaign have highlighted supermarkets and bread companies it names for producing or selling sourfaux that include “Aldi, Asda, Coop, Dr Oetker, Hovis, Lidl, M&S, Morrisons, Sainsbury’s, Tesco and Warburtons.”

I don’t think that sourdough is the preserve of the middle classes, and I am delighted to be involved with industrial bread manufactures, consulting and seeing real sourdough process begin to improve the nutritional profile of industrial bread, but I do still hold that correct labelling is necessary, and I will be watching with interest to see the new self regulated packaging.

In the mean time you can read the new regulations on sourdough by the ABIM here. on a personal note I am delighted. I have read the regulations and I feel they are fair, and will make a difference to the direction of sourdough as the regulations seem respectful of the working in their outline.

Real protection for real sourdough?

January 2016

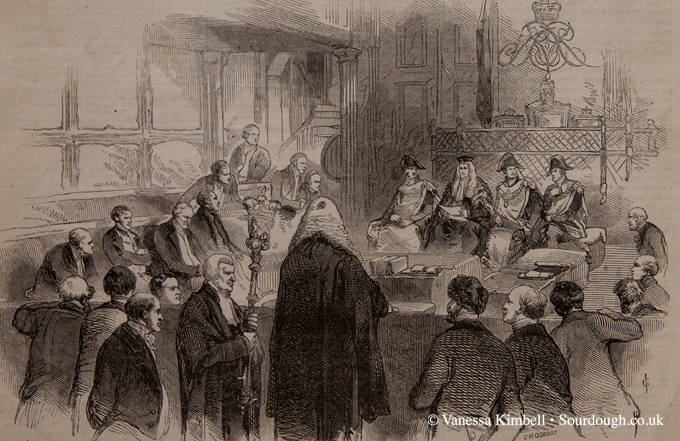

I met last summer with my MP Chris Heaton Harris. He is my neighbour and his daughter babysits my children. Chris is amazing and we sat in my kitchen as I explained the way I teach baking as lifestyle medicine. Chris was brilliant in listening to the evidence on how sourdough can potentially benefit heath and in the Summer facilitated a meeting with George Eustice, head of DEFRA,

So last week I took my sourdough starter to London, to a second meeting with the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA) and I so invited the Real Bread Campaign to come with me.

Why does sourdough need legislating?

Sourdough bread has come to the forefront of the British food movement in recent years. Artisan bakeries are thriving and sourdough has had a huge renaissance. Yet whilst we celebrate all that is good and wholesome about sourdough and even cheer the demise of cheap flaccid commercial sliced (I hesitate to use the word bread here) loaves there is an insidious and perverse practice emerging from the commercial sector of fake sourdough. It is utterly wrong that these loaves, made using dried inactive powders, flavouring, emulsifiers, commercial yeast, artificial acidifiers, preservatives and a fast-tracked fermentation, are allowed to be called sourdough, given that my work in in teaching and using the sourdough transformation of flour during the fermentation process as part of the approach to teaching baking as preventative heath.

I first made sourdough over 30 years ago and until recently there has never been a need to protect sourdough, but in the past few years, leaps in manufacturing processes means that sourdough is being faked and consumers are being conned.

The traditional way of making sourdough is thousands of years old. It is made with a culture made of water and flour in which naturally occurring wild yeasts and lactic acid bacteria have been nurtured into populations that are then substantial enough to leaven the dough. It is then fermented slowly. It is this trio of fermentation time with the yeast and bacteria that s is what gives sourdough its unique properties of digestibility, the bioavailability of minerals and potential to help manage blood sugar levels. * see references below.

As it stands the UK regulations means that both the labelling and marketing of sourdough gives no indication of the methods used or the length of fermentation. Manufacturers are selling “instant,” sourdough bread, which has had just a bulk fermentation of 40 minutes, and is “flavoured,” with sourdough powder. The purist in me is offended by the complete bastardisation of the immaculate relationship between wild yeast, lactic acid bacteria, flour, water, salt and time especially when artificial additives are then added to facilitate this process.

So how is it that the Chorleywood processing type corporates are allowed to hijack our most fundamental food? It is because there is no definition for sourdough and no legislation to protect it.

I wanted to find out what kind of legislation could be put into place to ensure transparency for consumers buying sourdough bread and how we can protect our most basic of foods from adulteration. THE DEFRA MEETING

The choices we discussed at length are as follows.

- (DEFRA suggested) Industry self-regulation

- Real Bread Campaign asked about a simple amendment of the current Bread & Flour Regulations 1998, or other existing food labelling legislation, to include a legal definition

- General guidance issued from the government similar to those issued in May 2015, by The Food Safety Authority of Ireland for The Use of Food Marketing Terms, as direction to make sure that consumers are not misled by the use of marketing terms on foods.

- Registering sourdough bread as a Traditional Speciality Guaranteed

None of these solutions are ideal.

It is very clear talking to the “ industry” that regulation isn’t something they are afraid of.

DEFRA indicated that getting ministers to agree to a “ simple,” amendment to the bread and flour regulations was anything but simple. It involved getting the attention of minsters and this was discouraged on the basis of the current policy of avoiding red tape.

The second option of guidance is just that. It is not regulation and so is no better than the current situation.

Could a designation for sourdough result in more harm than good?

The third option of registering Sourdough as a Traditional Speciality Guaranteed seemed to be DEFRA’s preferred option. It is, however, not ideal and not at all straightforward.

In the first instance, this would mean validation. This means a body would have to administer a system that audits bakeries. There is such irony that in protecting consumers through a Traditional Speciality Guaranteed name would mean more money, more time, more paperwork and compulsory membership to a body to be able to sell sourdough. It seems to me that this would suit a large corporation very well, but the small artisan bakers, who are after all the ones mainly making real sourdough just do NOT need this extra cost and admin in order to sell what they already make! As a member of the soil association which is a very comparable governing body to the kind that would be needed to allow bakers to then use the word sourdough, we do about 3 hours of paperwork a week and the true cost with admin and following procedures is about £2500 a year. So if this were to be the case using the word sourdough, then many of the small independent bakeries baking now might no longer be able to afford this option. They would no longer be able to afford to call their long slow fermented bread sourdough

For large commercial producers, this would simply be another administrative procedure.

Could a designation be a threat to small bakeries making sourdough?

I wondered who would regulate the validation? Would the realbread campaign who I invited to attend the meetings be converted into a regulatory body? Would sucess in changing the current Bread & Flour Regulations then mean they had completed their purpose? These are questions that I haven’t got the answers to.

The big question for me is wondering if small bakers that support a campaign for designation of sourdough would be quite so keen for any kind of reform of they fully understood the potential financial and time demands on them for this option?

We were also advised that by registering the word sourdough itself would result in serious challenges to the definition of sourdough. Manufacturers will present a case at the consultation stage arguing that there is no definition, and so their faux version is also sourdough.

It was then suggested that we use a prefix. “Real sourdough,” which as quickly was dismissed for the same reasons that “Sourdough,” would be challenged. The most easily (not that any of this is easy,) name to protect would be the name “Traditional Sourdough.”

It will take years and full bread industry consultation to get this option to Brussels.

No ideal option

I left DEFRA headquarters with my pot of sourdough with a sense that they wanted to help, but also feelings of complete frustration at the irony of the lack of choices for real protection for real sourdough. I’ll admit swearing along the lines of “stick that,” in the pub (only stronger) afterwards with members of the #realbread campaign, and know now that it was naïve of me to think that the systems in place could or would be used in the best way possible to help to protect something, that rightfully belongs to all of us, in the form it is has always been in. I cannot see any artisan baker wanting to sign up to an auditing body that enables them to call their sourdough “ traditional sourdough?!” In fact, it does totally the opposite of what I set out to achieve allowing the word “sourdough,” completely free for the fakers to use indiscriminately!

I’m afraid that the advice to use a prefix to differentiate sourdough from this mass-produced additive-laden instant fodder has left me outraged. This is the preferred option to protect the sanctity of authentic sourdough?

This offer to prefix of the word “traditional” is the soft option. It is a pacifying manoeuvre. An offer designed to sooth the artisan bread movement. A feel better sticker, that we can pop on our window, like a child getting a star on their homework, with the words good effort. It is a hollow offering. A solution that ruffles no feathers. I see this for what it is … a cheap fix which essentially allows totally impunity for corporates continue to manufacture rotten corrupt false sourdough that manipulates, exploits and takes advantage of the efforts of generations of artisan bakers, who make one of the most honest foods available naturally to mankind, and for what?

When I mentioned this option to a sourdough baker on the phone that night their sense of incredulity left me holding the phone a good distance from my ear for several minutes until he had calmed down. “ Surely fairness would be to make the fakers call their produce “ sourdough flavoured?” he said.

You would think so.

At this point in time, I can see 3 ways to go forward.

Do nothing which relies on consumers differentiating between sourdoughs through information provided by the media and bakeries that bake real sourdough, in the way that it has always been made.

To accept a Traditional Speciality Guaranteed protected name and really fight for the word “Sourdough,” with no prefix – and accept that this means auditing in order to administer it.To fight for a change to the bread a flour regulations. This would mean a national campaign, and getting minsters attention in order to secure a regulation like the French already have for the use of the word sourdough (with their Décret n°93-1074 du 13 septembre 1993.) This would mean real protection with no paperwork required and no costs and no membership needed for anyone, which would also mean that there is a level playing field for all bakers.

In the end, it will not be down to a handful of people to make a change. The level of protection we end up with will be down to just how passionately people really feel, and whether or not they are prepared to stand up and fight for the rights of our most fundamental food.

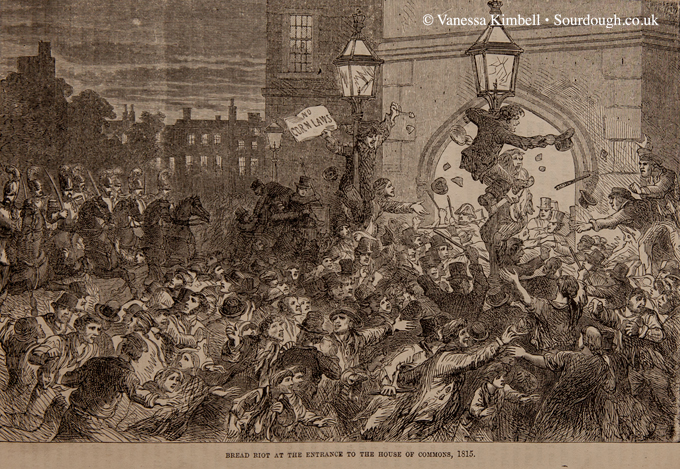

I’m afraid that the only way to make this happen is for the public and the bakers to rise up, which if I am honest will need considerable support from everyone, including the media. The French are prepared to do whatever it takes when it comes to protecting their culture and heritage and food. So the question is are we prepared to fight to protect our recently revolutionised British bread culture?

I will not support any other option other than a change to the current Bread & Flour Regulations

I don’t believe that any other destination than a simple amendment of the current Bread & Flour Regulations 1998, or other existing food labelling legislation, to include a legal definition is a way forward. If you feel the same please let your MP and DEFRA know that real sourdough bread really matters.

My advice is to be clear if you support the real bread campaign which of these options you support. You can and find further details in the additives and labelling and sourdough sections of the Real Bread Campaign website www.realbreadcampaign.org

www.sustainweb.org/news/jan16_defra_loaf_labelling/

•Sources

Sourdough and cereal fermentation in a nutritional perspective. Poutanen K, et al. Food Microbiol. 2009.Show full citation

How the sourdough may affect the functional features of leavened baked goods. Gobbetti M, et al. Food Microbiol. 2014. Show full citation

Sourdough fermentation of wholemeal wheat bread increases the solubility of arabinoxylan and protein and decreases postprandial glucose and insulin responses Jenni Lappi et al. Journal of Cereal Science 2010 Show full citation

The Tea That We Drink & Use…

The Tea That We Drink & Use…

I love bread. I have my own starter and love making and eating the stuff I make.

I absolutely understand that big business see the sourdough “brand” as an opportunity to make even more profit and that, as things stand, ordinary people will be the losers.

Of course legislation is a possible way to protect sourdough, but such an outcome may just see the supermarkets etc., back out of that particular market. Another approach (separate, or run in parallel), is to promote better bread.

I’m constantly shocked at the poor quality of bread that the UK consumer is prepared to put up with. It is time that there was a country wide campaign to improve bread quality across the board.

I might be wrong, but I’m convinced that large scale manufacturers of “bread”, including the supermarkets, have developed processes that produce a very poor quality product indeed. Given that making decent bread is not really that difficult, and given that the process involved (or indeed the ingredients) are not that different from the current practice, I’m puzzled why at least one of them does not break ranks to actually make good, wholesome, family bread.

The solution is obvious, us progressive breadheads, need to recruit a Jamie Oliver, Hugh Fearnly-Wittingstall or some other high profile campaigning foody, to spearhead a real industrial bread campaign – and not only pressurise the industry but educate the consumer.

If that ever got off the ground, real sourdough would not need protecting.

Such is the sad truth when it comes to modern food production. It is always the small, genuine businesses that are forced to “prove” that their product is the real deal. The same is true of words like “artisan”, “craft” and ” handmade” Trading standards laws should have enough teeth to weed out the imposters, but, as ever, public demand for food at unrealistic prices leads to our USP s being adopted as marketing tools to sell cheap counterfeits at a price which could not possibly return a profit for the genuine article. The result is very much what we see in the organic sector, with expensive, time consuming paperwork and audits together with a plethora of self appointed ( and highly profitable) bodies demanding all manner of conformities in order to use an appellation that should, by rights be the assumed standard, rather than bodies ensuring that anything less be declared larger than life for the consumer to see. The consumer drives demand. If they want to know badly enough, they will ask, but most of us have had our sense of value conditioned by supermarket pricing and our palettes dulled by mass produced foods to the point that we don’t recognise what constitutes “real” anymore. I dare say many people would reject a truly free range chicken as tough or chewy and a truly handmade sourdough as too expensive. Therin lies the greatest tragedy.

I just want to say, THANK YOU FOR BEING ON THE CASE!

Sorry to be cynical here but if as a consumer you can’t tell the difference then you probably don’t care enough to track down the good stuff. Thosecwho do care will probably only ever buy a maximum ofone crappy fake loaf!

Hi Andrew, in principle I agree, but the fake stuff is actually really well done. So much so that when I looked at the loaves in an artisan bakery in The Yorkshire dales in August I was fooled. It looked, and smelt like sourdough. I sent a picture to a fellow baker and he tipped me off that this was a fake mix. I was amazed .. so I went back the bakery, asked the assistant if I could take some photos of the bakery, as a touriset and low and behold there was a stack of instant sourdough mix sacks. The bakery even had ” award winning,” artisan bakery certificates in the door. Now … if it can fool me, then it can fool anyone.

I think that is what horrified me that most, and what actually drove me to speak to my MP and DEFRA.

Reading your article, it does seem as if the French legislation option is the best way forward. I don’t want people to think that sourdough is merely “flavoured” bread, obtainable, as Lyn says above, from the bakery section of a supermarket. I see no reason why there should be qualifications on the term ie “real” or “traditional”. That is plain wrong — it needs the term protecting in law and I suspect the French were pretty strict on this kind of thing given their general passion for food and drink.

I must say that now I have at least one baker (within walking distance!) who sells excellent sourdough, I no longer feel impelled to come back from France with bread. (I do bake my own but sometimes the professional stuff has that edge!) Although when I am at my Dad’s, we will sit round the table discussing the merits of the several local bakeries and their breads, viennoiserie, patisserie etc. It’s a very soothing discussion especially when accompanied by samples.

Thank you for taking this up with DEFRA. I don’t necessarily trust them as all too often the people with whom they consult are from the major food corporations who only are interested in the bottom line. I will certainly write to my MP about this to see if there is anything they can do or indeed, if they are interested in helping.

Emma (previous post) is spot on, you need a campaign. A proper, full on, national campaign run by a top PR company that knows how to get into people’s heads. A campaign that will give people the information they need, and, most importantly, the questions they need to ask when buying bread. Only sufficient pressure from the general public will bring you the change you want. Look at different types of crowd funding, angel investors etc.

Thank you for your post. Very interesting to hear about the options, or lack of them. I wonder if fighting for really comprehensive labelling of ingredients would be another help. The faux sourdough are generally found in the bakery sections of supermarkets, where bread is not labelled. If they had to label all the ingredients consumers may soon learn to distinguish between real and fake breads. I have asked for ingredients in the past, but also know they don’t need to declare them all- seems clear to me whose interests are being served with such policies.

Hello Vanessa,

How utterly frustrating… thank you for standing up and trying to make change happen though.

I am passionate about sourdough and one only needs to see the reaction from people who eat proper, real sourdough for the first time, to understand that this bread does deserve protection.

I set up Wild Baker a little over a year ago to teach people how to make this fantastic bread at home and absolutely love the response and feedback I get from them. It’s so rewarding to open people’s eyes as to what bread can, and should, taste and feel like. It’s an absolute outrage that sourdough can be hijacked in this way by corporates who just jump on the bandwagon.

Anyway – I was moved to write to say “thank you” for trying to make a difference to this disgraceful state of affairs and also to offer my support in this matter – I was a corporate lawyer in my previous life, so if there is anything I can help with on that or any other front, please know that I would love to.

It’s great that we’ve got a fight going to protect sourdough. It’s really important after all the great work that the real bread campaign has done that charlatans are not allowed to piggyback on this. If you’d like to use our festival to promote your work we’d love to have you here.

Hi Paul,

I’d love to .. can you message me your contact details please?

Thanks

Vanessa

I think the best way to get what you want, ie real protection for the use of the name Sourdough. Is to try to get a celebrity chef on board. And start a campaign like Hugh Fearnly -Whittingstalls campaigns on waste and fishing quota’s.

In fact I’d say he’s the one you’d want. Certainly trying to appeal to MP’s sense of justice and desire to do the right thing is a waste of energy, most of them have no interest at all in what is morally right, or what benefits the citizens of this nation.