It is hard to find rare or unusual grains to mill. I didn’t want to just mill wheat, but all kinds of grains such as Einkorn and Emmer and Barely. In early 2011 as I looked for these grains I met John Letts who was able to help me learn more about these many different kinds of grains not just wheat, that we once grew.

My journey to understand how things have changed so much brought me full circle. From baking sourdough loaves using the very first wheat we gathered 10,000 years ago and then went on to cultivate, through the history of bread and the industrial revolution, to the genetic manipulation of both grain and yeast, on to the development of chemical chemical cocktails now needed to both grow and process modern wheat, and then I found myself back at the beginning, looking at the very first wheats we domesticated. It is a sad story, and one that explains how, in less than a century we abandoned both the flavour and nutrition of our most basic food, in favour of producing vast amounts of cheap industrial bread; but along the way I discovered the secret to baking the most delicious, nutritious and environmentally sustainable bread there is….

The more I researched into the history of bread the more I wanted to understand diversity and . The evidence of numerous scientific studies and first hand accounts show that the ancient methods of fermenting bread fundamentally change the effect that bread has on our health and well being. Sourdough is easier to digest, it is more filling and nutritious, There is no doubt whatsoever that the loss of using long slow fermentation had a huge part to play in in the increase in problems digesting wheat over the past fifty years, but what quickly became apparent was that there was much more to the story than the fermentation process alone. The grain with which we make our flour had a large part to play in the story.

When I discovered, a rare pamphlet about how to effectively use beer barm to leaven bread, dated 1770, I decided to reproduce the bread. The beer barm was easy enough to find, but finding 18th century flour wasn’t. I was fairly certain that the kind of flour that was being used 240 years ago wasn’t going to resemble today’s modern flour. It took me a few months to find a source of heritage flour but, in spring 2013, after quite allot of detective work I discovered a miller called John Letts at his farm who had spent a lifetime cultivating heritage grain.

listen to ‘John Letts heritage grain specialist ’ on audioBoom

John Letts Lammas Fayre

//

John Letts of Lammas Fayre flour was taken with bringing ancient grains back to life after some grains found in a thatched roof caught his eye. He has been all over the world and spent the past twenty years collecting and growing heritage grains and milling heritage blends of flour. His passion and knowledge of ancient grains captivated me. As you can imagine I was really delighted to find that he had an 18th century blend of flour, which then meant that I could bring the recipe to life and in baking the bread I discovered that bread milled from ancient grains was that heritage flour is utterly delicious. In terms of flavour, it quite literally knocked the socks off modern flour.

What I found even more remarkable was, that these grains are nutritionally superior and environmentally more relevant today than ever, which had huge appeal to the food activist in me. As I looked at the bundles of wheat in Johns barn I saw that ancient wheat was much taller than the wheat grown today and many of them had the most beautifully complex ears. They were nothing like the short stubby and uniform wheat we see nowadays.

Heritage grains are robust. They stand tall, and have adapted over thousands of years. In contrast to modern varieties, they are genetically diverse with very deep root systems, which means that they grow on marginal land, without any irrigation, pesticides, or fertilizers. In comparison to the genetically identical wheat of today the ancient varieties are often more far more resilient to both climate change and pests than modern varieties. This also makes them an environmentally sustainable crop as it avoids using fertiliser.

John explained to me that to use modern fertiliser would be a disaster for heritage grain. They already grew tall to out compete weeds, but adding modern fertiliser would make the wheat grown far too tall. Fertilizer would also burn the mycorrhizae. These essential fungi grow in association with the roots of the wheat and exist by taking sugars from each plant ‘in exchange’ for moisture and nutrients gathered from the soil by the fungal strands. The mycorrhizas greatly increase the absorptive area of the wheat, effectively acting as extensions to the root system. When phosphorus is present in insoluble forms in soil ( as it often that case) it would require the grain to have vast root system to meet it’s phosphorus requirements so the symbiotic relationship with the mycorrhizas is crucial in gathering this element in marginal soils, allowing wheat to prosper.

It’s somewhat ironic when you stop to consider that before we started manipulating wheat nature took care of things.

The deep root system also means they can seek out resources in the soil that are not available to shorter modern wheat, which has to rely on the same 8 inches of top soil year in and year out. So in many instances heritage flour is also nutritionally far superior to flour made with modern grain.

John explained that all grains were like this until the industrial revolution when almost overnight everything changed as two distinct technological revolutions happened simultaneously. I started looking for more evidence of how our bread has changed and you can quite literally put dates on key moments, which have lead directly to the modern day problems of wheat digestibility that we face today.

John generously shared his flour with me. He gave me his heritage blend, his Elizabethan Maslin blend and Rivet wheat, which was first introduced by the Normans in the 11th century. As I began to experiment and compare my sourdough bread it became apparent that over the past century we have sacrificed both flavour and nutritional value of our flour in favour of texture and yield.

Unfortunately, at the time of writing, John’s Lammas Fayre wheat isn’t available to buy. However, it lives on through Miller’s Choice wheat, grown in Suffolk. This wheat variety was first developed by Andrew Forbes of Brockwell Bake, who used his London allotment as a testing ground, pairing Lammas wheat with a Spanish tall grain to create a truly flavourful variety, now available to buy from DeliverDeli.

I am thrilled. This development of The Lammas Fayre wheat means that flour from almost every key period in history is now available to bake with. It is quite possibly the most exciting thing to happen to flour since the industrial revolution because bakers are now able to recreate the textures and the flavour from key periods in history.

My imagination has no limits. We can eat the kind of bread that Queen Elizabeth I ate as she listened to news of the defeat to the Spanish Armada, or bake the kind of bread that William the conqueror ate before going into battle, or even make the kind of fermented fruit cake shared with queen Boadicea and her daughters.

There is real joy in baking really delicious sourdough bread that is nutritious and easy to digest, as well as being a sustainable food that enriches the environment. The secret to the most delicious, nutritious and environmentally sustainable bread there is, is to bake sourdough bread with heritage flour.

The possibilities are endless, as bread has come full circle.

I believe that it is our fundamental right to enjoy wholesome bread that is not destructive to either our health or our environment, and baking real bread is a revolution, that anyone can be part of.

Click here to book a course to learn to bake using heritage flour with Vanessa Kimbell.

//

A list of Sourdough Courses, Classes and Workshops in the UK and Ireland

A list of Sourdough Courses, Classes and Workshops in the UK and Ireland

Very nice article and well done. This is our first year growing heritage grain and are enjoying exploring both wheat and barley.

Ours is an organic small farm that practices agroecological approaches. Still learning, not perfect.

Thanks for sharing.

Thank you for sharing let me know how your harvest goes – it is soon right?

Vanessa

This is a fascinating read. I was drawn to this article because I have, for the first time, made a 100% wholewheat spelt loaf with John Letts’s Roman Blend; and a sourdough fruit loaf with the Victorian Blend. The flavour of the finished loaves blew me away and so I instantly googled it to find out more about it. I was very happy to read that this heritage flour is nutritionally superior to modern strains, too. Having tasted these flours, it will be difficult to return to my usual brand.

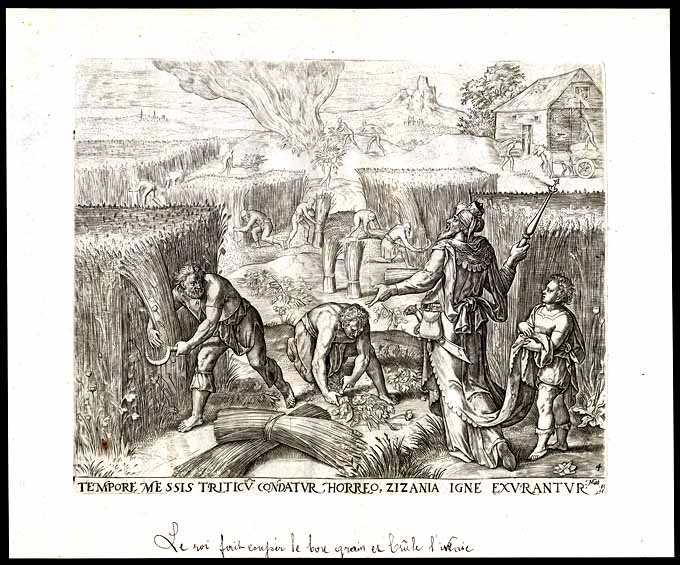

Hi interesting article untill you tried to make it hinge on how wheat was taller then. With that illustration from the 1500s. There are 3 men and one boy .the only man standing is a head higher thean the wheat the other 2 bending are also taller. When you consider the average height in the 1500 was 5ft. Your whole argument falls apart. Its always the small details that catches people out.

Hi David,

You are right, people used to be shorter. But heritage wheat is significantly taller. It’s always hard to include every tiny detail in an article, but I have a couple of hundred photographs of wheat in my collection from mid 15th century onwards and all of the photos show that wheat is about 4 feet tall. The height of the straw was a huge asset as it was used as building material, especially in thatching. I also spent time comparing heights with John Letts, the UK’s leading heritage grain grower and his wheat is very tall. Hope that helps.

I will try and upload a few more photographs of heritage wheat.

Wow! Hope that heritage flour ships to California. Bravo Vanessa!

What a wonderfully informative article. I really admire the determination of people like John who are dedicated to literally keeping these heritage grains on our planet. I often reflect on how nature seems to outcompete our so called technological breakthroughs. Its great that Bakery Bits have been prepared to run with this too and with your help make the grains available to bread making enthusiasts. Many thanks to you all

This is fantastic, and I love the idea of your historical breads. I personally bake with sourdough, and have tried a few old grains (well , kamut and einkorn) and felt that I still couldn’t tolerate or digest — but maybe the thing would be to give bread a long rest then come back to it and being really strict about both old varieties AND long fermentation and see if my sensitivity had waned. Love your work, can’t wait for your book!

ps re-reading, saw that it’s possible to buy these wheats, which I shall do! Congratulations on this amazing project.

Hi Annie, Thanks for the lovely comments. It’s certainly worth a try. There are studies that show that different grains have different levels of gliadin which are worth reading as there is evidence that this is more of an aggravating factor in some people. If you do find a grain the you can tolerate then you can further blend it with gluten free flours such as buckwheat too.