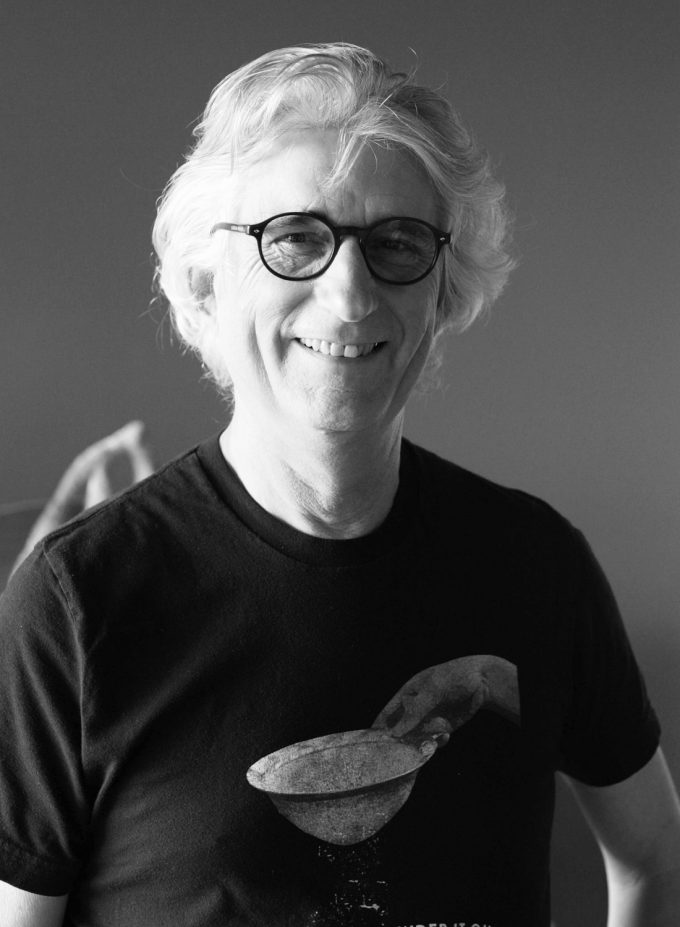

Michel Suas – Founder of the San Fransisco Baking Institute

No baker wakes up one morning knowing how to bake. It takes time, and practice and inspiration and I have worked with and met many bakers over the years. There are some bakers that stand out more than others. The ones who influence and change an industry to such an extent that you can see, or even, taste reflections of their work on bakery counters all over the world.

Michel Suas is one of those bakers, and immaculate presentation and attention to the tiniest detail are some of the recognisable traits I spot in the patisserie of bakers who have been taught by Michel. In 2016, I was fortunate enough to meet and spend some time with Michel in San Francisco at the San Francisco Baking Institute (SFBI), a baking school and consultancy that he founded with his wife, Evelyne, almost 25 years ago. I loved chatting with Michel Suas; he’s incredibly knowledgeable about all things related to bread making. Articles about Michel in the American media generally refer to him as a ‘baking guru’, but what they might not tell you is that he’s also kind. I say this because, when he realised that I was stuck without a ride, he drove me back into the centre of San Francisco in rush hour. It was in the opposite direction to his home at the end of a long day, and we chatted in the car for almost an hour and a half on the highway, in French.

Michel arrived in San Francisco just as the artisan bread revolution was beginning in the city. His background and experience – he had trained as a chef, pastry chef and baker in France – meant he was soon in demand as a bakery consultant. In fact, Michel’s list of clients reads like a who’s who of the San Francisco baking scene. His first client was Steve Sullivan, who had founded The Acme Bread Company a few years earlier. Michel used his expertise to help the bakery as it expanded. Through this work, he was put in touch with Nancy Silverton at La Brea Bakery and went on to advise Chad Robertson of Tartine when he was opening his first bakery in Reyes Point Station, and Thomas Keller when he opened Bouchon Bakery.

Explaining how he came to set up the San Francisco Baking Institute, Michel says, ‘I realised there were a lot of people who were involved in the baking industry, but they didn’t have as much knowledge as they should have.’ He was inspired by the passion Californian bakers had for bread making – ‘I thought it was a good wave to catch on,’ he says – and this was enough to encourage him to stay. Having worked his way through the French apprenticeship system and baked bread for a 3-star Michelin restaurant, Manresa, Michel Suas was well trained in classic baking techniques and was ready to share his knowledge. ‘We opened the school with no sponsorship because we wanted to have the freedom to teach whatever we wanted,’ he says. One of the ideas driving the school was to give small bakeries and keen amateurs access to the help they needed, without them having to pay for one-to-one consultancy.

The SFBI is now a destination for bread-making students from all over the world. Some are wanting to set up their own bakeries, some are already working at bakeries large or small, and some are home bakers with a thirst for knowledge. The courses run at the school focus on equipping students with the theory and practical techniques they need to be able to expand their baking ideas, rather than just teaching them the formulas and processes for specific recipes.

After I’d been in the city for only short time, I realised that sourdough there is so iconic they simply call it ‘sour’. There has been much written about what makes a real San Francisco sourdough, with bakeries across the world producing their own version of the loaf. Michel explains that the really sour acidity and leathery crust, characteristic of the San Francisco sourdough, is down to the way the mother is maintained, the proofing techniques, temperatures and timing, and even the ovens used to bake the bread. ‘They use a high-protein flour, and they ferment the mother in a cool temperature,’ he says. This favours the production of acetic acid and keeps the pH low. Michel contrasts this with the approach taken in France. ‘The French usually do that [ferment the levain] at room temperature, with a little bit more water, and the flour protein is not as strong. So you have a little bit more lactic acid’, he says. He feels that in San Francisco, the focus is on using the levain to make the bread sour, whereas in French bread making, the focus is more on getting the bread to rise: ‘If you look at the two breads, one is really dense and one is a little chewier.’

Having been involved in the development of so many great bakers and bakeries, Michel has been able to watch as the artisan bread movement has changed over the years. He has seen more small retail bakeries open to cater for a growing demand for good bread, especially as younger, professional people have moved into the city. ‘The bakery used to be a place where you go in the morning, buy your bread, then go home,’ he says. ‘Now the bakery is like a club or a bar; you go there in the day and have a tartine or a sandwich and a pastry.’ Bakeries are opening with coffee shops attached and have become a place where customers can relax, socialise and enjoy something to eat. As Michel says, ‘The bakery adapts to their lives.’

Michel has also watched with interest the growing use of heritage grains. ‘At the San Francisco Baking Institute we have been working with ancient grain for many years,’ he says, ‘and now it is becoming more mainstream.’

Like me, he felt that these grains, when made into doughs that are given a long fermentation, produce breads that can be eaten without discomfort by people who have difficulties in eating bread made from regular wheat. This is something they had noticed at the Baking Institute, but had been waiting for someone with the necessary scientific backing to confirm.

Talking with Michel was an absolute pleasure. I learned so much from him in the space of a short conversation.

If San Francisco isn’t in your immediate travel plans, but you’d like to learn more about Michel’s approach to bread making, he has written a book – a very big book – called Advanced Bread and Pastry. It was created for the Baking Institute and is more of a textbook than just a baking book, but well worth reading. There are also a series of short and incredibly informative training videos, which are accessible through the website for an annual fee.

How to Apply for a Course & Other Questions

How to Apply for a Course & Other Questions

Hello Michel,so finally able to see you ..